19 August 2021

This article was guest written for Ending Loneliness Together by Hugh Mackay, social psychologist and researcher, and the bestselling author of 22 books including his latest, The Kindness Revolution, published by Allen & Unwin.

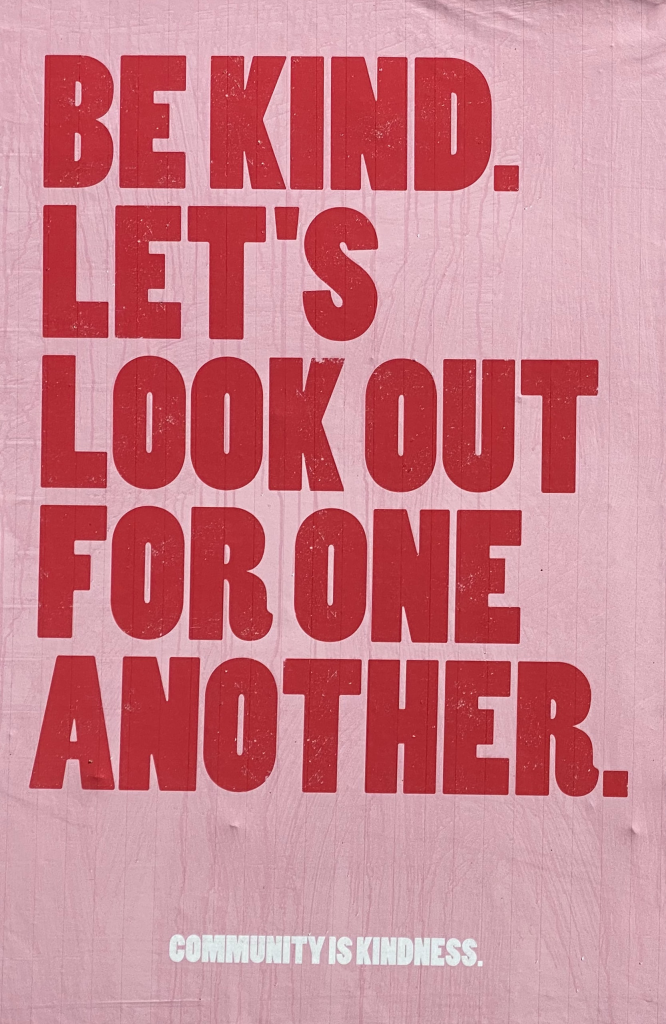

To understand the health hazards of loneliness and the healing power of kindness, we need only reflect on the nature of this species we all belong to. We humans are members of a social species which means, in essence, that we’re hopeless in isolation. We need each other.

We need families, neighbourhoods, groups and communities of all kinds to nurture and sustain us and to give us the all-important sense of ‘belonging’ that is so fundamental to our mental and emotional health. Indeed, our very survival as a species depends on our ability to create and maintain social harmony.

Like all herd animals, we suffer when we are cut off from the herd. Yes, we all need solitude; we need time to ourselves for replenishing our resources for the demanding business of being a member of a social species. But too much isolation heightens the risk of loneliness, anxiety and depression – along with other health hazards like hypertension, inflammation, cognitive decline, disturbed sleep and vulnerability to addiction.

“Kindness is the universal balm for troubled souls. It’s not only the best way for non-lonely people to reach out to those at risk of loneliness; it’s also the best way for the lonely to find a pathway back to connection and belonging”

So it comes as no surprise to learn that neuroscientists have identified a ‘co-operative centre’ in the brain. As you would expect of a social species, we are genetically equipped to co-operate, to congregate, to share.

That means, in turn, that we are all equipped with an innate capacity for kindness, since kindness is the key ingredient in the creation of co-operative, harmonious communities. As the American bio-neurologist Donald Pfaff says, ‘We are hardwired for the Golden Rule’: our default position is to treat others the way we would like to be treated.

Kindness is the universal balm for troubled souls. It’s not only the best way for non-lonely people to reach out to those at risk of loneliness; it’s also the best way for the lonely to find a pathway back to connection and belonging. Kindness takes the focus off me, and puts it squarely on the needs of others, and that’s a healthy way to live. Ancient wisdom has always said so, and contemporary psychology confirms it.

“I see you; I hear you; I accept you as you are”

What is this thing called kindness? It’s anything we do to show another person that we take them seriously. Because we are social creatures, that need to be taken seriously – to be recognised, acknowledged, included – is the deepest of all our social needs. And it’s a need that can be met by something as simple as a smile or a greeting as you pass someone in the street, or an offer of a chat over a cup of coffee. At a deeper level, it is met whenever we listen attentively and empathically to someone, when we offer a sincere apology for having hurt or wronged someone, and when we forgive someone generously. All such behaviour conveys the unspoken message that ‘I see you; I hear you; I accept you as you are.’

Kindness is perhaps the noblest and purest form of human love. All forms of human love – romantic, familial, companionate – are wonderful, but kindness is unique in that it requires no feeling of affection, nor any emotional response to the other person. When we are being true to what Abraham Lincoln described as ‘the better angels of our nature’, we are capable of acting kindly towards people we don’t like, people we could never agree with, and even people we don’t know.

As Samuel Johnson wrote, 250 years ago: ‘Kindness is in our power, even when fondness is not.’ Isn’t that a lovely thing to know about this species we belong to – that we all have the capacity for kindness towards anyone, including total strangers? (And isn’t the kindness of strangers one of the loveliest things you’ve experienced?).

Our capacity for kindness is our most precious human asset, yet we don’t always value it as we should. We may sometimes brush it aside in favour of more ego-driven impulses: unbridled ambition, for instance, or ruthless competitiveness or acquisitiveness, or rampant individualism. But when kindness prevails, we flourish!

If we are born to connect, to co-operate and to show kindness towards each other, then here’s a remarkable thing about our society: the social trends that have been reshaping us over the past 30 or 40 years have been pushing us in the opposite direction. Far from becoming more socially cohesive, we have actually been becoming more socially fragmented. Far from becoming more conscious of our interdependence and interconnectedness, we have become more defiant about our sense of independence, our individual differences and our uniqueness.

A quick reminder of some of those trends:

Even that short list is enough to alert us to the cumulative effect of such trends: more fragmentation, less cohesion, more social isolation. And because we belong to a social species, these trends are producing the predictable effect: the rise of the Me Culture (exemplified in our current obsession with ‘identity’) and the three epidemics that inevitably follow the atomisation of a society: loneliness, anxiety, depression.

Our differences become irrelevant as we rediscover the importance of the neighbourhood. We tend to display more kindness and concern for others’ needs; we become more alert to those at risk of social isolation; we acknowledge the need to make personal sacrifices for the common good.

But COVID-19 has added a new twist to the story of our social evolution, by doing what crises and catastrophes always do. Whether it’s a war, a bushfire, a flood, an economic depression or a pandemic, major disruptions to our way of life serve to remind us that we exist in a shimmering, vibrating web of interconnectedness. Our differences become irrelevant as we rediscover the importance of the neighbourhood. We tend to display more kindness and concern for others’ needs; we become more alert to those at risk of social isolation; we acknowledge the need to make personal sacrifices for the common good. Yes, there’s often a bit of fear and panic in the beginning, but those ‘better angels’ usually prevail.

The question is: has this disruption to our way of life been enough of a shock to act as a circuit-breaker, mitigating the effects of those anti-social trends, or perhaps even slowing them down?

People who survived the Great Depression of the 1930s sometimes looked back and said, ‘It was the making of us’. Not that they enjoyed the deprivation and hardship, the prolonged unemployment, or the anxiety about putting a meal on the table for their kids. No; they were talking about lessons so deeply absorbed that they never left them. Values clarified. Priorities re-ordered. A recognition of what really matters.

Through the pandemic, and especially through the lockdowns, we, too, have learned some lessons – about looking out for neighbours (especially the frail and elderly), about the hazards of social isolation, about the attractions of de-stressing and simplifying our life, and about the limitations of IT. Will those lessons stay with us? If we liked ourselves better when we were kinder and more respectful towards each other, why not stick with that as our way of being in the world; our default position; our daily practice?

If we dream of a world that’s kinder, more compassionate, more respectful, more co-operative, less violent, less cynical and more harmonious – a world where loneliness, anxiety and depression are no longer found in epidemic proportions – there’s only one way to make the change: we must each start living as if it’s already that kind of world. If enough of us live like that, that’s the kind of world it will become.

With thanks to Hugh Mackay for this article. You can read Hugh’s latest book, The Kindness Revolution, here.